We know that demon do not swallow the sun during eclipse but, there is no dearth of excitement and curiosity around this natural occurrence. The spectacular cosmic opera that unfolds before us during total solar eclipse still enthrals us and the fact that we now know more about the cosmos mechanic does not make it any less exciting. From holiday companies selling solar eclipse packages to eclipse chasers to drift through the clouds in cosy comfort of an airplane to get an up close and personal view of this cosmic drama, to cottage industry of safe solar goggles sellers all make brisk business over a short span capitalising on curiosity of people, kept alive since the beginning of time. If modern man still finds it captivating and is compelled to experience this wondrous cosmic drama, pause, and think about the hunter gatherer societies….what they made of this sudden disappearance of sun, black night engulfing the earth in middle of a day. It is quite natural that in their simplistic way they assumed someone has eaten the sun!!

To modern man it’s the Moon coming between the sun and earth but to the ancient man across most civilisations it was a call of doom and gloom. Every civilisation from India to Mesopotamia to China to Egypt viewed this temporary disruption of natural rhythm as an ominous sign…some sinister events to unfold in future.

As far as eclipse myth goes there’s a common theme that runs across all myths – that of a demon devouring the Sun. In some cultures the demon takes the form of a giant turtle as it is in Vietnam, while in Romania it takes the form of werewolf , or a dragon in Asia, a jaguar in Latin America, a serpent in Egypt so on and so forth. Not having the scientific knowledge and tools, ancient man was unable to understand that eclipse is very much part and parcel of the natural rhythm of the cosmos. They sought to explain, in their own way, this disruption of natural order, spun stories of doom and gloom, which expressed their fear and insecurities but most importantly their limited understanding of the physical world.

The guide’s voice carried on behind me, in front of me were my excited daughter and husband racing fellow tourists across a stretch of grassy meadow… I was at Olympia, gazing at some marble blocks embedded in the earth that had been excavated first by German archeologists in the 19th century! These marble blocks, worn down by the ages and elements were the actual starting blocks for the historical Olympic Games that started sometime around 776 BCE and continued every four years till they were abolished by the Roman Emperor Theodoisus I in 393 AD. The sheer ‘drama’ embedded in the history of the place itself is enough to give even the most hardened onlooker a few goose bumps. But when one spins back and lets one’s mind wander off to the mythic origin of the games at Olympia, the sense of wonder and marvel is multiplied. For here on these plains, one can experience a continuous chain of ritual unbroken from the time of the mythic hero Herakles to the recorded history of the ancient four-yearly games in Greece’s ‘Golden’ classical age to the torch-lighting ceremony that is practiced during modern Olympics Games right here in the 21st century!

The mythic origin of the Games goes such: Herakles, that greatest of Greek heroes, the son of Zeus was celebrated throughout the lands for his ‘mythical’ physical strength. It was he, who established the games at Olympia and decreed that Greek men from all the city-states should meet on these plains every four years to participate in many ‘sporting’ feats as a way to honour Zeus. Our guide further informed us that legend says that Herakles inaugurated the games at Olympia and was present himself to act as an ‘umpire’. It was Herakles who instituted the ritual of honouring the victors with an olive wreath, a tradition which was continued till the 4th century AD!

So Olympia and the Games are, in a way, a classic case study for the myth-ritual branch of academic discourse. What is a historical fact is that scholars can trace back the games in Olympia to as early as 776 BC! Whether the myth of Herakles honouring his father, Zeus was a myth created to sanctify the ritual of this sporting event or whether the enactment of this wonderful celebration of the human body’s striving to transcend ordinary physical constraints was a rite designed to bring alive the achievements of Herakles and other heroes, it is for scholars to decide.

The ‘marble’ proof of the mythic association of Herakles with the ancient Olympia games is preserved today in the museum at Olympia. These are the fragments of the sculpted metopes that depicted the Labours of Hercules and decorated the Temple of Zeus that stood outside the sports stadium at Olympia! In fact, some scholars say that the Olympian metopes were probably the first instance when the twelve ‘Labours of Hercules’ were grouped together and recorded for posterity!

Though finding comparable myths and spotting their parallels in rituals etc. is among the greatest joys of the amateur ‘student’ of mythology, the Olympic Games are in fact quite unique and have very few parallels outside Ancient Greece. Some of the points that distinguish and tie in the tradition of the Olympic Games from other such ancient practices are:

• This is a ritual designed to honour the Father of the Gods but is in its essence quite secular. While a temple was built in Olympia dedicated to Zeus(in fact, it housed one of the ancient wonders, the magnificent towering statue of Zeus by Phidias) which attracted votive offerings from far and wide, the main significance of the Olympian plains was demonstrating ,celebrating and honouring exceptional physical feats by men.

• Closer to home, we have the example of the ‘swayamvar’ a mass display of exceptional male physical prowess. But in this case the reward was material, the princess and through her power and the throne. The Olympic Games on the other hand were all about honour and glory. The only ‘material’ reward was the olive wreath for the winner while the fame and prestige that the athletes won throughout the land was the real inspiration.

• To my mind, the most singular aspect of the games at Olympia was the democratic and inclusive principles on which they were founded. The Herakles myth does not detail any conditions that the great hero laid down for participation. And the recorded history from the 8th century BC is clear on one point- to start with, any able bodied Greek man could take part, whether king or noble man or peasant. While restricted to only Greeks, after some centuries, participation was extended to men from the colonies and later in first century AD even to Romans. Surely, this level of democratisation was quite unique in those ages of antiquity. Think of the discrimination faced by one of the greatest heroes of Indian epics, Karna. When Karna came face to face with the Pandavas first time in the arena where the royal princes were showing off the skills they had learnt from Drona, his superb talent in matching Arjuna’s skill, was not applauded by all. Instead, Kripa stepped forward and mocked Karna as he was not a known Kshatriya and of uncertain parentage. Even after Duryodhanna crowned Karna the king of Anga, some versions of the Mahabharata recount how at Draupadi’s swayamvara, the princess herself demurred to let Karna try his hand at the contest as he was not of royal birth. Contrast this with the Olympic games: even though the mythic founder, Herakles, was of semi-divine parentage, the games were open to all Greek men above a certain age!

• However, the democratic foundations of the mythic and ancient games were not absolute. Neither Herakles nor the Ancient Greeks were imaginative enough to allow women to participate. Nor were slaves permitted. Though the Olympia site is unique in that, next to the magnificent Temple of Zeus, there stood a temple of Hera, it seems that women were permitted only to take part in introductory rituals such as the lighting of the torches. A tradition that is kept alive to this date- when every four years the modern Olympic Torch is lit at Olympia by women and is then carried by sports stars, other icons and others to the actual venue. Women were not even allowed to be spectators!

Someone wise once said that the Greeks modeled all their Gods on themselves and not the other way round (unlike later Christian doctrine where God created Man in his image). The Olympic ritual exemplifies this ideological foundation beautifully! The Gods of Olympia could race faster than the wind, fly and seemed not to be bound by any of the physical limitations of the human body! The heroes like Herakles who were usually semi-divine actually took on the gods and occasionally triumphed. And finally, you had the citizens of the Greek states run, jump, wrestle, use javelins and iron balls almost too heavy to be lifted, on the Olympian plains every four years to show the Universe and Nature, that the human body can be trained, can be pushed to achieve feats almost miraculous and thus reach heights that can only be imagined for the Gods.

I am glad to have had the privilege to stand on the grassy tracks that witnessed the feats of countless athletes who participated for the glory of nothing but an olive wreath because this event symbolizes one of the earliest expressions of what it is to be human! I can think of very few other rituals/events/myths wherein people strove, pushed themselves, competed not for the spoils of war or conquest or riches – but just because as humans ‘we can!’

RUKMINI GUPTE

The stories that we tell shape our lives and define our roles within our communities. They are incredibly powerful. And if we want to create change – effective sustainable change – it is these stories that we need to change.

Have you ever wondered what happened to the narrative of women? How is it that the woman started off as the supreme goddess worthy of worship and ended up at the bottom of the food chain? What changed?

The story begins with woman as the goddess and she was the goddess because she had the ultimate power – she could create life. That was the ultimate miracle and that is what made her worthy of worship.

Ironically as time moved on it was not her story that changed – after all she still creates life – is the way the story was told that changed. Woman no longer created life because she could or because she wanted to but because she was told that she had to, she was told when and she was told with whom!

Her ability to create life was no longer seen as her power but her duty as a subservient being. This was now the weapon with she was to be dominated.

The same things that made woman the goddess are now what make her the slave. It is not the story that changes but how you tell it. It is the tiniest little shift in the story.

Interestingly, every 1000 years or so, a revolution seems to take place in the narrative of women. We can trace a pattern of renaissance, a kind of resurgence; like the crest of a wave which attempts to overturn the existing stories of disenfranchisement and retell them as they were to begin with—an empowering narrative. At the turn of this millennium we are once again in the midst of a narrative revolution and whether by accidental birth or by the design of karmic rebirth we are the women into whose laps this renaissance has fallen. In the cycle of events it is an extraordinary time to be around because now it is we who must decide how to change this narrative.

It is time to look at our stories – and I would like to begin with this tiny story….

In the Hindu traditions of North India on the morning of the wedding the bride is given a set of red and ivory bangles to wear. They are arranged in a set except for one extra white bangle that sits on the outside of the set which is known as Gaurja ki Choorri (the goddess Parvati’s bangle). When I was getting married I remember asking the priest what that extra bangle meant and he told me that the bangle was a bride’s prayer to the goddess Parvati to grant her a husband just like goddess’s own husband.

Now I had to wonder about this. The goddess’s husband Shiva, though a great God (and I am sure many wonderful things in his own way) is not an ideal husband by any stretch of imagination. He drinks, he indulges in narcotic habits, he keeps the worst kind of company, he disappears for months on end because he wants alone time. He is a hermit so doesn’t believe in jewellery and nice things generally. I mean why would I want to pray for a husband like him?

So it took a bit if research but I finally found out – yes, that extra bangle is a prayer to the goddess but the prayer says ‘please give me the strength to love my husband even if he is like yours’. (Alf Hiltebeitel)

Now that’s a story that makes sense

Incidentally there is a school of thought that women want a Shiva-esque man – the thrill of the ‘bad boy’ syndrome. This story teller would like to hear your views.

On Women’s Day today, there is the usual outpouring of celebratory messages, whether on the Google doodle or on Facebook or on chain SMSes etc…. The world is saluting our gender’s strength, creativity, compassion, fortitude – but, as in any other narrative on women, I struggle to find any references to a woman’s ambition that is unconditionally laudatory, without any undertones of prejudice or censure. So even today as speculation is rife on whether Hillary Clinton will run for the US Presidential elections or on the various headline-grabbing references to Anushka Sharma being the most stunning WAG for the men in Blue (never mind that she is a very successful professional in her own right), the discourse on women can never be conducted with focus on her ambitions, her goals alone! Probably the only woman in the public sphere who has succeeded in transcending this “trap” is “Didi” or West Bengal’s Mamata Banerjee. Much as I disagree almost entirely with her politics, I have to admire her drive and ambition that saw her realize power on her own terms in a country where women ascend to the “throne” only on the strength of dynasty or marriage or patronage from powerful men (like Jayalalitha or Mayawati). And I wonder if it’s pure chance in the universe’s systemic chaos or whether there is a socio-cultural and regional pattern that enables this singular expression of femininity in my home province. For, surely, one of the most unusual and arresting mythic personas from the countless myths and legends of India, is that of Manasa,the “Snake Goddess” of Bengal..an almost unparalleled mythic expression of an “anti-establishment” feminist ambition and power!

I remember reading, with a mixture of fascination and curiosity, many tales in Bengali about Manasa and her epic rivalry with Chand Saudagar. The latter epitomized patriarchy- a merchant prince, who had the power of his gender, of capital and patronage from the most powerful male deity of all, Lord Shiva. Manasa, on the other hand, was a lone “woman” who had command over the netherworld of snakes and serpents and her own unbridled ambition, and with these resources, she waged a relentless campaign for respect and recognition. Somehow even as a child, I realized that in the many versions of this tale that I read, there was always an overt and in some, a subtle tone in the writing, that underscored Manasa’s cunning, her rage, her ambition in a less than empathetic way. The final straw in the narrative is the introduction of Behula- the archetypical “Sanskritized” feminine role model- a woman who will sacrifice everything, including her life, to resurrect her husband, because she becomes significant only as a wife. As long as the myth is a rollicking adventure chronicling the tempestuous turns of the struggle between Chand and Manasa, the audience can still choose to take sides! But, the masterstroke of the patriarchy is to bring in the pathos of Behula-Lokhnidor and no wonder, audience sympathy will then be forced away from Manasa to Behula!

However, it may be topical today as debate rages on in India about women’s security and entrenched patriarchal violence against women, to remember and understand Manasa as a genuine feminist icon. Her myth signifies many anti-establishment profiles:

• A non-Aryan , lower socio-economic class cult struggling for patronage from people while up against upper caste Brahminical prejudices

• A semi-divine female confronting the established patriarchy, be it the divine Lord Shiva or the temporal capitalist authority of Chand Saudagar.

Manasa raises uncomfortable questions on the role of feminine energy when faced with male power and authority. From her birth ,Manasa has had to battle for her dues- Shiva first refused to recognize her ,though she is said to have been fashioned out of his seed! She is a great source of energy, but unlike the Sanskrit Mother Goddesses, Manasa’s power has a sharp, vindictive edge! She does not hesitate to resort to trickery, coercion or brute strength to subvert her enemies. And if that is par for the course and praiseworthy attributes of the great patriarchal male heroes of our Puranas and epics, then why not laud the same in Manasa too?

And the most significant aspect of Manasa, that I personally feel is worth celebrating, nay, even passing on to India’s Daughters today is that Feminine Spirit and Energy ,which is not shy of pursuing self-interest and ambition even at the risk of being deemed too aggressive or unfeminine!

So on this March 8, as one of India’s most talented sports icons, Saina Nehwal (who has always demanded to be judged just as an athlete not as a woman athlete), faces a great challenge at All England Open tournament, I say to my daughter and all her friends- go forward, find your goal and unabashedly pursue it and disdainfully ignore those carping voices who think there should be boundaries and limits and curfews and codes to transcribe a woman’s ambition!

With the Navaratri, Debi Paksha and Durga puja festivities coming to a close, people across India are celebrating the victory of good over evil. But I couldn’t help pondering about what would the goddess be without a demon to slay? What would Ramayana be without Ravana, or the Pandavas without the Kauravas, or Bhakta Prahlad without Hiranyakashipu and one can go on. Mythology is replete with stories about gods and demons in conflict, where the demons represent evil, epitomise malice, mischief, malevolence and every form of wickedness and the god or the goddess, stands for good slays the demon and reinstates social order.

Mythology we must remember is the science of primitive man; it was his manner of explaining the universe. And right from the beginning of time man was intrigued by the existence of the opposite forces – of good and evil, life and death, darkness and light, heat and cold, rain and sunshine, and the eternal struggle and dynamics that exist between these polar opposites. These forces and related phenomena took anthropomorphic forms, the benefactors or beneficiary forces as gods and goddesses and the rest, became demonic powers. (Of course, quite often, a present day god has begun his or her life as a destructive force. Prayer was an act of propitiation to start with, before it became a form of obeisance).

Demons challenge the existence of gods and humans alike. Human inability to comprehend and control these forces led them to create myths of supernatural power, trickery and magic and thus demon loosely started representing forces beyond human control and comprehension, one who has control over the negative aspects of the both material and spiritual world.

Demonisation also gained currency as nomadic Aryans marched into the subcontinent and found indigenous tribes with customs and practices very different from their own. The Aryans had to fight them to establish their relative superiority and to survive in a foreign land. And as indigenous tribes came to be known as Dasa, Dasyus, Danava, Asuras, leaders of the winning team were deified.

But an important facet of the gods and demons conflict is that they are always seen as equals, born from the same mother. They are both sons of Prajapati. Demons are often learned and worshipful even of the gods (Ravana an ardent devotee of Shiva) and they are also the recipients of boons of immortality or invincibility which leads them astray and becomes the cause of their downfall.

The battle between the two is also seen in myths as a battle between dharma and adharma. Durga slaying Mahisasura, Indra versus Vritra, Rama Versus Ravana, Krishna versus Kamsa, these are all instances of the triumph of the right order over the wrong one. But could we ever bring forth goodness without contrasting it with an opposing evil? Good in the universe is valuable only when it co-exists with evil; goodness on its own purposeless.

Gods and demons, good and evil are interdependent as are creation and destruction, light and darkness, life and death, they are not mutually exclusive but inclusive and one without the other is incomplete, the missing half of a whole. The battle fought between the Gods and demons is a quest to resolve tension of opposing forces, with opposing claims and interests and above all, the struggle for survival, an effort to achieve an ideal order, dharma. As a hero needs a villain, gods need demons as there would be no gods without demons, no one to save the world from evil forces and bring equanimity.

A few kilometers before Auroville, between the spiritual vibes and the foreigner-made Goa feel there is a small village with no significant name of its own. Perhaps as a visitor I have not cared to look for the name of the village. But by the side of a sharp turn in the road, I notice this small temple with a lot of idols. They cannot be missed because like in many Tamil Nadu temples, these idols also are painted in enamel colours. These anthropomorphic images are highly impressive with their rose bodies and multi-coloured costumes. I could have regarded this as one of those temples and invested my gaze into the silent wonders of nature around. But what attracts me is the main idol that lies down on the ground under a canopy, with guarding votive figures around it.

By the time I could take the details in my car has crossed the temple. Hence, while coming back I ask the driver to stop at the temple. I get down with my small camera and walk into the premises. I am very impressed by what I have seen there.

The signboard done in flex board says that it is ‘Arassummoottil Sree Ankala Parameshwari Amman Aalayam’. I look at the main idol that lies on the floor. It is the idol of a goddess and I recognize her as a Devi figure. Later researches prove that she is one of forms of Parvati worshipped in the Southern part of India. She is called Ankala Parameshwari. Ankala means Universe. This goddess who rules the universe. And she is in a relaxing posture after she danced to kill. According to the myth of Ankalamman it is said, once five headed Brahma performed a yagna to save men from two demons Sandobi and Sundaran. From the fires of yagna came Tillotama, an apasara who mesmerized the two demons by her beauty. To save herself from the clutches of two demons Tillottama fled towards Kailasa, followed by two demons and Brahma. When Parvati saw Brahma with five heads she mistook him for Shiva and feel at his feet. But when she realized the truth she was angry and prayed to Shiva asking him to destroy Brahma’s fifth head. Thus Shiva assumed the form of Rudra and beheaded Brahma’s fifth head.

Angry and humiliated Brahma cursed Shiva that his head would get attached to his hand and thereby Shiva would be affected by hunger and lack of sleep. Shiva as Kapalika- i.e. one with skull in hand, roamed the earth, slept in graveyards and smeared ashes over his body and started begging for food. Whatever food he would get the skull or Kapala began to eat most of it. Meanwhile Parvati was unable to bear her husband’s misery. She approached her brother Lord Vishnu and pleaded him to relieve Shiva from Kapala. Lord Visnu told her, “My dear sister, go to Thandakarunyam graveyard with your husband and make a pond there and name it “Agni Kula Teertham” then prepare a tasty food made by “Agathi Keerai” mix it with the blood and spread that food around the graveyard. With the smell of blood, Kapala would leave Shiva’s hand and eat the food. Then take your husband to the pond and wash him clean with waters so that Kapala would not get stuck to his hands again.”. Parvati did as her brother said and when Kapala got detached from Shiva’s palms she cleaned him with the water. When Kapala came back to Shiva it could attach itself, but now it attached itself to Parvati hand. She became so furious with anger and began to dance. As she danced she grew in size. bigger and bigger till she covered the universe. In this gigantic form she crushed the Kapala with her right foot. Only then she lay down to relax on the ground to relax.

In this fiercest form which destroyed Kapala, and which came out of Parvati is called Ankala Parmeshvari or more fondly as Angalaamman. Parvati then asked Angalaamman to stay in the same place and serve the people.

Ankala Parameshwari is worshipped in different parts of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. In some places she is worshipped as a pregnant goddess. And most of the pregnant women from these regions travel to Ankala Parameshwari Amman Alayam for healthy children and painless delivery.

There is a beautiful mutative blend of Shaivite and Vaishnavite cults in this temple. The guarding angles of Ankala Parameshwari are the incarnations of Vishnu. And interestingly most of them are in the female form. So you see a Narasimha moorty and Varaha in female forms. Even the mutations of the cults are shown in the Ardhanareeshwara.

This particular village temple is called Arasummoottil because there is an arasu tree in the premise. And one interesting idol that I find is a small sculpture of a tortoise kept under a tree. And before this tortoise figure there are a row of bricks kept vertically smeared with turmeric powder and kajal. There are yellow threads running around it.

Women constitute majority of devotees in this temple. What interests me is the celebration of femininity and feminine principle including pregnancy as a centre of worship in this temple. Without controversy the transformation of male incarnations are made into female incarnations. This I feel is like a reading of the male scriptures from a female point of view; a sort of discursive cult that challenges the male point of view without breaking much of the ideologies built around the Hindu temples.

Story Collected by : Johny M L

Source: as told by locals

Location : Tamil Nadu

Last week on Women’s Day, there was the usual outpouring of celebratory messages, whether on the Google doodle or on Facebook or on chain SMSes etc… the world saluting our gender’s strength, creativity, compassion, fortitude. But, as in any other narrative on women, I struggle to find any references to a woman’s ambition that is unconditionally laudatory, without any undertones of prejudice or censure. So whether it is an analysis of ‘grandmother’ Hillary Clinton’s readiness to run for the US Presidential elections or the various headline-grabbing references to Anushka Sharma being the most stunning WAG for the men in Blue (never mind that she is a very successful professional in her own right), the discourse on women seems never to be conducted with focus on her ambitions and goals alone! Probably the only woman in the public sphere who has succeeded in transcending this ‘trap’ is ‘Didi’ or West Bengal’s Mamata Banerjee. Much as I disagree almost entirely with her politics, I have to admire her drive and ambition that saw her realise power on her own terms in a country where women ascend to the ‘throne’ only on the strength of dynasty or marriage or patronage from powerful men (like Jayalalitha or Mayawati). And through these random ramblings on women and power, I am reminded of a singular character from the world of myth, whose assertiveness and formidable will is almost unparalleled in the female cast of Indian mythical characters. For, surely, one of the most unusual and arresting mythic personas in our mythic tradition is that of Manasa, the ‘Snake Goddess’ of Bengal–a vivid expression of an ‘anti-establishment’ feminist ambition and power!

I remember reading, with a mixture of fascination and curiosity, many tales in Bengali about Manasa and her epic rivalry with Chand Saudagar, the latter epitomized patriarchy. He was a merchant prince, who had the power of his gender, of capital and patronage from the most powerful male deity of all, Lord Shiva. Manasa, on the other hand, was a lone ‘woman’ who had command over the netherworld of snakes and serpents and her own unbridled ambition, and with these resources, she waged a relentless campaign for respect and recognition. Somehow even as a child, I realised that in the many versions of this tale that I read, there was often an overt and in some, a subtle tone in the writing, that underscored Manasa’s cunning, her rage, her ambition in a less than empathetic way. The final straw in the narrative is the introduction of Behula- the archetypical ‘Sanskritized’ feminine role model, a woman who will sacrifice everything, including her life, to resurrect her husband, because she becomes significant only as a wife. As long as the myth is a rollicking adventure chronicling the tempestuous turns of the struggle between Chand and Manasa, the audience can still choose to take sides, but the masterstroke of the patriarchy is to bring in the pathos of Behula-Lokhindor into the tale. No sooner is that done, audience sympathy is forced away from Manasa to Behula!

However, it may be topical today as debate rages on in India about women’s security and entrenched patriarchal violence against women, to remember and understand Manasa as a genuine feminist icon. Her myth signifies many anti-establishment profiles:

• A non-Aryan , lower socio-economic class cult struggling for patronage from people while up against upper caste Brahminical prejudices.

• A semi-divine female confronting the established patriarchy, be it the divine Lord Shiva or the temporal capitalist authority of Chand Saudagar.

Manasa raises uncomfortable questions on the role of feminine energy when faced with male power and authority. From her birth, Manasa has had to battle for her dues- Shiva first refused to recognize her, though she is said to have been fashioned out of his seed! She is a great source of energy, but unlike the Sanskrit Mother Goddesses, Manasa’s power has a sharp, vindictive edge! She does not hesitate to resort to trickery, coercion or brute strength to subvert her enemies. And if that is par for the course for and leadership attributes of the great patriarchal male heroes of our Puranas and epics, then why not laud the same in Manasa too?

The other interesting characteristic of Manasa is her independence. She may be born from Shiva’s seed but does not get any support from that illustrious divine lineage. There are references to her marriage with the powerful sage Jaratkaru in the Puranas. But in the principal source of the Manasa legend in the Bengali Manasamangalkavyas(thought to have been composed between 13th to 15th centuries), Manasa is a ‘lone warrior’. She fights for recognition from the ‘Establishment’, personified by Chand Saudagar on her own terms, with her followers (the snakes) and her own resources. She does relent finally, impressed by the steadfastness of the mortal woman, Behula and expresses her power by bestowing the greatest gift of all, life to Lokhindor. In return, she extracts the promise that Chand will be persuaded to worship her (albeit with his left hand). But that’s enough to win her a seat in the pantheon of deities venerated by the ‘establishment’! How refreshing this–the calculated negotiation by a determined goal-oriented ‘Goddess’ who uses her power to extract her dues rather than give it away in selfless benevolence that females are always expected to display.

In today’s Bengal, after centuries of Sankritization, the cult of Manasa survives in pockets but the ‘fighting spirit’ and commanding authority of Manasa has been subsumed in a gentler and more stereotypical deity who is about wish fulfillment for childbirths and prosperity. But maybe the time is right for us to re-appraise the true significance of Manasa. I personally feel it is worth celebrating, nay, even passing on to India’s daughters today, Manasa’s Feminine Spirit and Energy, which is not shy of pursuing self-interest and ambition even at the risk of being deemed too aggressive or unfeminine!

Our society is going through rapid change and in no sphere are the changes as ‘unsettling’ as in the roles and expectations from women. And while men, women, parents, guardians, one and all grapple and come to terms with these changes, it is our daughters, who need to be empowered with the confidence and self-belief that it is all right to choose one’s own path, whatever that might be. And it in this context that Manasa’s untiring quest for her rightful place can be an inspiring role model: choose your goal, whether conventional or ground-breaking and then, unabashedly pursue it and disdainfully ignore those carping voices who think there should be boundaries and limits and curfews and codes to transcribe a woman’s ambition!

The story of Siri (read The Epic of Siri) could be that of any woman in India. It is not the usual legend with a dramatic narrative featuring demons and magic and mystery, nor is it a description of a new order established through a heroic act. It is a story about ordinary people and their ordinary lives, a tale about husband and wife, co-wives, and sisters and their domestic quarrels and jealousies. It covers three generations and is a grim tragedy that could befall any woman. So why do Tuluva women still sing and ‘perform’ this story as a ritualized drama?

Siri holds an important position among the Tuluvas community from South Kannada district of Karnataka. They consider her to be the founder of Tuluva matrilineal tradition. Siri paddanas or the sacred recitations and the accompanying ritual dramatization take place annually in the form of a festival. Siri jatre or Siri alade as it is called, takes place on the full moon of paggu (February) in six different temples around the South Kannada region. It is believed that the spirit of Siri possesses women who are emotionally or psychologically ‘troubled’ due to various reasons. These women enter into a trance singing Siri paddanas.

Kumara is the only male character in the story and he acts as the priest/medium, talking to the women in a trance and asking them to identify themselves with the various female characters from the legend. He repeatedly asks, ‘Tell me who you are? Are you Siri? Or Sonne? Tell me why have you come? What is troubling you?’ The dialogue takes place in the form of a ritualized impromptu song-speech. He then conducts a ‘spirit investigation’ (Clause: 1991) to discover the reason for the women being possessed. At this stage, the women, having identified themselves with the characters of the legend, pour out the sufferings and grief that they have experienced in their lives while simultaneously narrating the tale of the characters they identify with.

Thus the ritual act gives them a cathartic space to temporarily forego their individual identities and step outside of their real life framework and vent their anxieties, anger, frustrations and unfulfilled desires. They are thus able to deal with the trauma inflicted upon them by family members, on account of their caste, due to class conflicts and sexual dissatisfaction.

The spirits speak through the possessed women and inform the people gathered as to why they have had to intrude into the lives of the young women. They extract a promise from the family members that they would resolve the domestic disputes that have been revealed during the trance.

At the end of the ritual women enter into a ‘grave’ made of areca nut leaves. This allows the novice – the young woman who had been possessed – to become a permanent member of the cult of Siri. She thereby joins the rank of other adept Siris and can return to the festival every year as an expert.

The question is does the myth and its accompanying ritual emancipate Tuluva women? Does it help them reclaim equity in financial and personal freedom as demanded by Siri in the legend? Noted Tulu scholar and anthropologist Prof Viveka Rai observes: ‘emancipation should be redefined by distinguishing between the point of view of the performer and that of the audience… Rather than considering ‘emancipation’ as a social activity of the outsider, I would like to stress here the transformation of mind and body of the performing women as a way of emancipation…how the performance of folk narratives and rituals contributes to bringing it about.’ (Shetty:2013)

According to French anthropologist Marine Carrin (2011), Tuluva women use the legend of Siri as a therapeutic tool to heal the emotional scars generated through societal and marital discords. American anthropologist Peter Clause (Ibid) summarizes ‘the major function of the cult’s rituals is to save defenseless women from quarrels and jealousies which arise within kin groups. While the women’s song tradition revolves around these (sic) sorts of problems and presents them as fatefully tragic truth, the ritual tradition, through the intercession of fictive male kinsmen attempts to alter and solve them’.

To conclude, the lore of Siri stands apart from other dominant patriarchal myths as it highlights the woman’s plight within her domestic space and offers a platform for negotiating and articulating her anxieties safely within a dominant patriarchal environment.

VIDYA KAMAT

References:

Carrin, Marine, “The Topography of the Female Self in Indian Therapeutic Cults”, Ethnologies, Vol 33, No 2, 2011, p. 5-28

Clause Peter, Ritual Transformation of a Myth, California University , East Bay, 1991

Rai, Viveka., “ Epics in the Oral genre system of Tulunadu”, Oral Tradition, 11/1 (1996): 163-172

Shetty, Y., “Ritualistic World of Tuluva: A Study of Tuḷuva

Women and the Siri Possession Cult”, Rupakatha Journal,

Vol. 5 No.2, 2013

History and controversy are no strangers to each other. And so it has been with the case of Aryans and the Indian subcontinent. Were they invaders? Were they the original inhabitants? There are hundreds of questions with thousands of answers. Still the debate continues about whether there was an Aryan invasion or was it a slow assimilation of two or maybe more cultures. In the absence of any conclusive evidence– archaeological, historical or textual–the Aryan Invasion theory largely remains within the realms of conjecture. The belief that there may have been a set of invaders has its roots in linguistic speculation and it gained popularity during the colonial rule of India in the nineteenth century. Max Muller was the leading proponent of the Invasion theory and it was re-iterated by the British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. But gradually, the interweaving of archaeological and linguistic data by scholars led people to question such an invasion. Also Max Muller proposed his Invasion theory in his early works but, contradicted the same in his later works and thus the theory gradually started losing steam. Over time theories of multiple small migrations that were less hostile and more assimilative started to evolve. Whilst linguists and historians engage various methods to back up their theories, each trying to impress the relative superiority of their methods, myths compel us to reach beyond our usual experiences and lead us into a world of interesting connections. As one peels away the initial layers, myths reveal hidden faces that lie underneath the seemingly childish and improbable stories that have been handed down to us.

At one level the stories reflect a changing social order and attempt to emphasise a moral code of conduct or at least indicate what should or should not be done. A careful read of some myths can lead to clear evidence of changing social and cultural order. They tell the tales of emergence of a dominant clan or class, of constant mutation of identities of indigenous and alien tribes. The stories indicate historical change, show signs of covert propaganda that must have been undertaken to establish the superiority of certain culture or clan. History is after all written by the victor. Therefore, whether or not there were physical Aryan invasions, leading to furious battles and blood shed, there was undeniably a cultural invasion with far reaching effects. The horse riding, migrating Aryan clans brought with them a new culture which in some cases took the dominant role and in others it fused with the indigenous culture, underwent mutation and took a new form. Also given that, three thousand years ago cartographic boundaries were not in existence and national territories and boundaries were fluid immense intermixtures happened through small scale migrations. Also society exhibited considerable social heterogeneity and hence the concept of alien and indigenous tribes needs re-examination.

In this constantly changing and evolving social and cultural landscape, the myth of Banasur and Jamdagni Rishi from Malana, in Himachal, the heartland of Aryan playing field tells us a tale of changing social order.

The story goes like this: Banasur was a mighty Raksasha who ruled very sternly over the area known as Malana in Kulu. To his kingdom came Maharishi Jamadagni with his wife Renuka. Jamadagni liked the sylvan surroundings and wanted to set up his hermitage in Malana. Now Banasur the wicked Raksasha had been oppressing his people a lot and did not welcome the rishi, rather he made up his mind to destroy him. Banasur was unaware that Jamadagni was a very learned man and had done years of tapasya. So he caught hold of the rishi and stuffed him in a huge cauldron full of oil, lit a fire under it and closed the lid. Several days later Banasur took the lid off and found the sage still alive and deep in meditation. Infuriated, he put the cauldron back on the fire and added more oil. Again several days later he opened the lid and found him alive and in deep meditation. Banasur was frightened and fell at his feet, penitent. The rishi agreed to forgive him on one condition: the Rakshasha should leave the area. Banasur agreed but begged that the peculiar dialect of the area, known as ‘Kanash’, not be uprooted. Jamadagni had no objection. He did not mind that Banasur would be remembered by his people through the language they spoke for, he felt, that every time they spoke, they would be reminded of the ultimate fate of wickedness.

Banasur left his kingdom but so great had been his oppression that the people were still afraid. They worried that he may return someday and wreak vengeance. So they made an effigy of Banasur and put it into a cage, which was locked up in a cellar (called ‘Raksa Ra Mord’). The idea was to destroy the effigy if Banasur returned as that would put an end to his life. The ‘Raksa Ra Mord’ is never opened and never will be until Banasur visits. Even today once a year a goat is sacrificed outside the cellar. Jamadagni Rishi, locally known as Jamlu Rishi is the reigning village god of Malana. The Kanash dialect although confined to the village Malana, still Iingers. It has no script and today only a handful understand the dialect but cannot speak it.

The story has many colourful threads, from Banasur as a fierce Raksasha king to Jamdagni Rishi, a flag bearer of Aryan culture and beliefs, and his emergence as the more powerful of the two; to preservation of the Kanash dialect of the region. Interestingly Rakshasas were once an indigenous tribe residing in these serene mountainous regions. Therefore the assumption that Banasur was a ruler of such a tribe doesn’t seem improbable. Painting Banasur as wicked, fierce and an oppressor, not only adds more colour to the story but also sets the stage for emergence of a deliverer, a redeemer who can rescue the oppressed people, bring justice and peace to the land. Who could better fit the role than Jamadagni Rishi, one of the revered saptarshis (seven rishis) and patriarch of Vedic religion and culture? Jamadagni’s victory over Banasur is both on the spiritual and physical plane. Subliminally, the story, justifies the change in social order, the outright cultural invasion by implying inferiority of the older order and that people wanted and welcomed the change and benefitted from it. Up until this point the story points towards apparent Aryanisation of indigenous culture but, it takes an unexpected turn when Jamadagni allows the original Kanash dialect to be preserved and spoken in the region. For, common knowledge tells us that cultural invasions lead to control over the conquered tribes through language. The story however implies that while different Aryan tribes sought to emerge as a culturally dominant race of the region they were not averse to assimilating with the indigenous cultures. It was a two way process—a bit of the incoming culture, a bit of the old and voila we had something new with different aftertastes. As two cultures clashed and battled it out to establish their relative superiority, the ways and beliefs of both cultures melded and diffused into each other. Perhaps it is this quality of the invader tribes that helped keep the region together and it still keeps us rooted to our sacred past and helps us maintain that most important unbroken link to our origins.

Sources

- The Aryan Recasting Constructs, Romila Thapar

- The Aryan Invasion theory final nail to its coffin, Stephen Knapp

- Gods of Himachal, B.R.Sharma

Oral tradition, the source of all folklore is now being celebrated as the chronicle of human history by providing evidence to the origin of people and their subsequent migrations.

The Nagas are a group of Mongoloid communities speaking Tibeto-Burman languages who inhabit a mountainous country between the Brahmaputra plains in India and the hill ranges to the west of the Chindwin Valley in Upper Myanmar. Unwritten, unrecorded oral traditions, such as folktales, folksongs, wise sayings, and proverbs are the primary sources of their legends.

The customs, beliefs, values, and opinions of the Naga society have been handed down from their ancestors to posterity by word of mouth or by practice since the earliest times. Children are taught about survival, endurance, and respect for nature and all mankind through stories and legends from infancy. Storytelling and folktales have been an integral part of Naga society. However, these oral narratives have been rendered into written form only recently. By documenting and recording folklore, social scientists are hoping to preserve pieces of the traditional and oral cultures of some of the tribes and sects being pushed to India’s margins.

The Mao Naga tribe inhabits the northern region of Manipur. Mao is a Manipur name which was also adopted by the British. Today, the more accepted view and opinion of the term “Mao” is from the Maram Naga tribe, akin to the Mao’s. The origin of the Mao Nagas is very obscure, and there is no written document of their past. The history and customs are preserved in their memories, and handed down from one generation to another only through oral narration.

As is typically the case with oral tales, the Mao story about the origin of Man leaves a lot of things unexplained. For instance, the story does not reveal how the first woman came into existence. As the earth represents the divine mother, symbolising the reproductive power of nature, it is taken for granted that the first woman is already there.

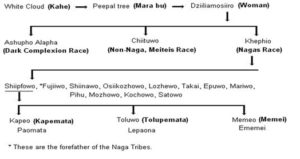

The myth says that all life forms originated from the first Mother, with the process of creation or conception initiated by an act of union with the clouds. Logically, therefore, ‘Cloud People’ should mean the whole of mankind. However, only the guardians of this legend, known as Maos, or Ememei in their own language, can be called the ‘Cloud People. Although the story is not widely shared by other Naga tribes (it is only prevalent among the neighbouring Angami and Chakesang Nagas), it forms a centre piece of an assortment of myths, which taken together tell the story of origin of the Nagas at Makhel. This tradition is reinforced by a wide range of relics and monuments at and around Makhel, and forms the foundation for the identity of the Maos as well as the Nagas.

In an alternate narrative (The original story can be read here), it is told that the white clouds came and enveloped Dziiliamosiiro and she conceived and bore three sons namely –

Ashiipfo Alapha, known as the forefather of the dark complexioned people, the Aryan and Dravidian races (Kolamei pfope),

Chiituwo, the forefather of the Non-Naga Meitei race (Mikrumei pfope), and

Khephio, the forefather of the Naga race (Nagamei pfope).

The myth goes on to say that Ashiipfo Alapha’s descendants settled down in the dark jungle (Ive katei) on the west (kola po). The descendants of Chiituwo (Meities) settled in the south valley (Mikrii po). The generations of Khephio (Naga race) spread and settled in the hills of northeast India and western Myanmar.

There is another tale about the origin and migration of the Mao Naga, which seems more recent. In this myth, the forefathers of the Nagas arrived from China. The ancestors are said to have fled when an autocratic Chinese emperor forcibly ordered his subjects to help in constructing the Great Wall of China. The ancestors quietly escaped and began walking upstream along the river Kriiborii, a tributary of Chindwin River in Myanmar, for a long time and finally reached the source of the river, hidden from the emperor and his soldiers. They decided to settle down there and named the place “Makhrefii.”(Makhre – secret, fii- place).

Mythology reflects the socio-economic, cultural and historical conditions of the community or society. Creation of myth is creation of meaning, and there can be many levels of meanings.

The above myth represents evolution rather than the creation. Tiger and Man represent the animal kingdom and Spirit represents the supernatural realm. The Myth tells us that all are related, since they are born of a common mother. Participating in the competition is quite natural as they are brothers.

In attempting to decipher the meaning of the myth, the question of truth and falsity does not arise. Tiger wanting to eat the mother after her death is perhaps the reflection of wanting to take her power and authority.

The woman represents reproductive energy. Her name signifying pure water, being fertilized by a cluster of clouds is perhaps a metaphor of the union between the sky-father and the receptive earth mother, from which all things have originated.

References

1. The Myths of Naga Origin By R.B. Thohe Pou

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mao_Naga

3. The Mao Naga Tribe of Manipur: A Demographic Anthropological Study By Lorho Mary Maheo

4. The origin of Tiger, Spirit and Humankind: A Mao Naga Myth by Dr. X.P. Mao

5. THE ANGAMI NAGAS With Some Notes on Neighbouring Tribes J. P. Hutton

6. Folktales of India, edited by Brenda E. F. Beck, Peter J. Claus, Praphulladatta Goswami, Jawaharlal Handoo

7. http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/naga

8. The Kingship System of the Mao Naga by Chachei

9. TRADITION AND TRANSITION OF MAO NAGA: A STUDY ON THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT by Komuha Jajuo and Tarun Bikash Sukai

10. Various oral narratives, songs, lectures and seminar proceedings

…Current Event…

….Recent events….

October-2022

September-2022

October-2021